-

Topics

backTopicsOur programs create spaces where open-minded leaders can gather for breakthrough conversations on pressing global issues – each aligned to one of the following pillars:

-

Events

backEventsExplore the variety of events Salzburg Global hosts within Austria and in the rest of the world. Learn more about our programs and what else happens at Schloss Leopoldskron.Upcoming EventsFeb 05 - Feb 07, 2026Peace & JusticeDisruption and Renewal: Charting the Future of the International Rule of Law, Democracy, and PluralismSalzburg Cutler Fellows Law ProgramApr 13 - Apr 18, 2026CultureCreating Futures: Rethinking Cultural Institutions, Infrastructure, and InvestmentCulture, Arts and Society

- Insights

-

Fellowship

backFellowshipSince 1947, more than 40,000 people from over 170 countries have participated in Salzburg Global's sessions. Collectively, these alumni are known as Salzburg Global Fellows.

-

About Us

backAbout UsSalzburg Global is an independent, non-profit organization committed to creating spaces that overcome barriers and open up a world of better possibilities.Our Approach

-

Support Us

backSupport UsYour generosity helps us gather open-minded leaders for breakthrough conversations, while creating space for dialogue that overcomes barriers and opens up a world of better possibilities.

- Donate

- Published date

- Written by

Share

General

Opinion

Why Mother-Tongue Instruction Remains Elusive in Nigerian Classrooms

Published date

Written by

Share

Photo Credit: Shutterstock.com/2051391749

This op-ed article was written by Thelma Obiakor, a writer in residence with the Salzburg Global Center for Education Transformation in 2025, and her colleague Adedeji Adeniran.

Despite achieving near-universal primary school attendance, learning outcomes in Nigeria remain alarmingly low. According to Adeniran et al., only 17 percent of students meet literacy competency standards, while 31 percent meet numeracy standards. One widely proposed solution to this learning crisis is to ensure that every child begins learning in their mother tongue. One widely proposed solution to Nigeria’s low learning levels is to ensure that every child begins learning in their mother tongue. At first glance, the rationale appears both straightforward and compelling: instruction is most effective when mediated through a language already familiar to the learner. This claim is further substantiated by decades of research consistently demonstrating the effectiveness of mother-tongue instruction across diverse contexts.

In Nigeria, however, the reality of language policy implementation is far more complex than the rationale suggests. While the country has adopted mother-tongue policies promoting instruction in indigenous languages at the primary level for several decades, dating back to the 1977 National Policy on Education (NPE), implementation has remained limited and inconsistent. For instance, only about 16 percent of early primary school pupils were taught in an indigenous language, despite more than three decades of official policy endorsing mother-tongue instruction. Such uneven implementation is unsurprising in a country as linguistically diverse as Nigeria, where estimates range from 150 languages to over 500. This persistent gap between commitment and practice underscores the multifaceted challenges that constrain the realization of these policies.

The SLIP Gap Framework: Challenges to Implementation

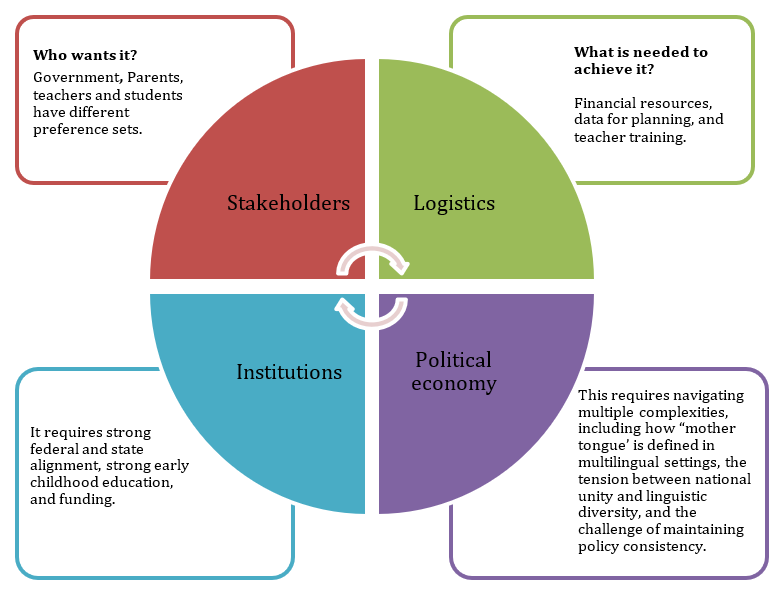

The implementation of mother-tongue instruction is constrained by several interrelated challenges that undermine its effectiveness in practice. These challenges cluster around four dimensions - stakeholder, logistical, institutional, and political economy. Collectively, these constitute what can be termed the ‘SLIP’ gap: A fitting acronym which captures how well-intentioned policies often “slip” between commitment and execution, leaving mother-tongue instruction inconsistently applied across classrooms. While this article focuses primarily on Nigeria, the SLIP gap framework is relevant across SSA, as many countries face similar constraints in their language policies.

Stakeholder Challenges

Parents, teachers, and students – the primary stakeholders in education - often hold preferences that run counter to policy goals. These attitudes, shaped by social and economic aspirations, frequently steer classroom practice toward English rather than indigenous languages.

Parental expectations are particularly influential. Studies from Nigeria and elsewhere in SSA show that parents consistently prioritize English, associating it with academic success and upward mobility. In some cases, resistance has been so strong that parents have withdrawn their children from schools using indigenous languages. This reflects a broader social perception that English opens economic and global opportunities, while local languages may limit them.

Teachers’ attitudes mirror these tensions. In Zamfara State in Nigeria, most teachers questioned the necessity of mother-tongue policy, reporting that pupils preferred English and viewed indigenous languages as irrelevant for international examinations. Yet these same teachers acknowledged that students were more motivated and learned more effectively when taught in their mother tongue. This contradiction illustrates how entrenched assumptions about English’s superiority can override recognition of the pedagogical benefits of indigenous languages.

Logistical Challenges

Beyond stakeholder attitudes, schools face practical obstacles relating to their material, infrastructural, and linguistic conditions.

Implementing mother-tongue instruction requires textbooks, teaching materials, and teachers trained to deliver instruction in indigenous languages – resources that remain scarce. Only 14 percent of surveyed teachers had access to relevant mother-tongue materials, while most primary textbooks, aside from language subjects, are written exclusively in English (Trudell, 2018). In practice, this forces teachers to rely on English-language texts, particularly in rural areas, and constantly navigate between English materials and local-language teaching.

Nigeria’s extraordinary linguistic diversity further complicates implementation. With more than 500 spoken languages, including three dominant indigenous languages - Hausa, Igbo, and Yoruba - alongside hundreds of minority languages, no single mother tongue can serve as a universal medium of instruction. Rapid urbanization and migration produce linguistically mixed classrooms, making it nearly impossible to assign one “appropriate” language of instruction. Even when indigenous languages are used, they may not align with students’ mother tongues.

Compounding these difficulties is the absence of standardized orthographies for many languages, which makes producing consistent materials and training teachers challenging. Governments also often lack reliable data on the distribution of languages across communities, further complicating assigning mother tongues to schools, particularly in linguistically diverse regions.

Institutional Challenges

Effective implementation requires a strong institutional foundation, with teacher preparation at its core. Yet Nigeria’s primary teacher training institutions remain disconnected from the realities of mother-tongue instruction. For instance, the abandonment of the Grade II teacher training system, once meant for preparing primary school teachers, has left universities and colleges of education as the main training route. Yet, these programs are generalized, producing educators for various levels without specific preparation for lower primary teaching, where mother-tongue instruction is most critical.

As a result, the institutional gaps in teacher education translate directly into logistical and classroom challenges. Schools face shortages of qualified teachers in the communities where they are most needed, and many available teachers lack both the pedagogical preparation and linguistic capacity to teach in the local languages.

The federal governance structure of education in Nigeria further complicates matters. While the federal government anchors mother-tongue policy through setting national standards, implementation is left to states that often lack operational guidance, monitoring mechanisms, or funding streams.

The Political Economy of Language Policy

Political factors create some of the most persistent obstacles to implementing mother-tongue instruction. These challenges are embedded in the way language policies are designed, interpreted, and contested within Nigeria’s multilingual setting.

A fundamental challenge lies in defining “mother tongue.” Nigeria ’s 2013 NPE mandates that “the medium of instruction in [all] primary school shall be the language of the immediate environment for the first three years in monolingual communities…from the fourth year, English shall progressively be used as a medium of instruction.” This formulation creates significant ambiguity. The very idea of a “monolingual community” is difficult to apply in practice, given Nigeria’s fluid and dynamic language use, and the policy provides little guidance on how to define the “language of the immediate environment” in multilingual contexts. In urban areas shaped by migration, children’s mother tongues often differ from the dominant community language, making it unclear which language should serve as the medium of instruction. Without clear definitions or mechanisms for interpretation, the LOI provision remains highly contested.

Another challenge concerns the national unity versus diversity dilemma. Since independence, English has served as Nigeria’s official language and is promoted as a “neutral” language of national unity, modernity, and progress. This ideology is reinforced through education policy, which encourages every Nigerian to learn English and one of the three major indigenous languages in addition to their own mother tongue. In this political climate, mother-tongue instruction struggles to gain support, as it is endorsed in principle but rarely enforced in practice.

Bridging the SLIP Gap

While the obstacles to mother-tongue instruction are well-documented, they often remain fragmented and discussed in isolation. The SLIP Gap framework proposes an integrative framework that captures the interconnections between different types of barriers and provides policymakers with a clear diagnostic tool. By emphasizing interconnecting challenges, the SLIP framework helps policymakers identify where reforms should be targeted. It highlights the need for coordinated reforms that tackle multiple interconnected barriers, offering policymakers and practitioners a clearer pathway for interventions.

The Salzburg Global Center for Education Transformation offers writing residencies at our inspiring home of Schloss Leopoldskron to thought leaders and educationalists working to advance the agenda of education transformation.

We invite partners who are interested in supporting these writing residencies to email Dominic Regester, director of the Center for Education Transformation at Salzburg Global.