Writer in residence Iman Albertini challenges ableism and bias to reimagine inclusive learning environments

This op-ed was written by Iman Albertini, who was a writer in residence with the Salzburg Global Center for Education Transformation in 2025.

In an era ruled by identity politics, we indulge in what Ellen Samuels calls "fantasies of identification" — a societal longing for definitive, legible identities that can be classified and confirmed through visibility. “I see it, therefore it is.” Within this visual economy of authenticity, disability becomes legible only when it is visible. The archetype of the disabled person - a white man in a wheelchair — anchors this fantasy, offering reassurance through its perceived clarity.

Non-apparent disabilities, ranging from neurodivergence to chronic illness, disrupt our certainties. They remind us that the body can be deceptive, that pain can be invisible, and that not all forms of marginalization are immediately legible. These realities threaten the hegemony of the visible and challenge our epistemological frameworks, especially those rooted in Western scientism, which privileges the tangible and the measurable.

Despite decades of advocacy from disability rights and justice movements, non-apparent disabilities remain overlooked — particularly when they intersect with other marginalized identities. Non-white girls with non-apparent disabilities occupy a position of profound invisibility. At the nexus of ableism, racism, and gender bias, they are rarely recognized, often misdiagnosed, and frequently unsupported.

This erasure is not accidental. Structural violence permeates healthcare and education systems alike. Non-white populations often experience limited access to diagnosis due to medical racism, socioeconomic marginalization, and deep cultural mistrust of medical institutions — mistrust that is justified. In many cultures, disability is still considered taboo, associated with shame or divine punishment, especially when it affects girls. These cultural narratives, though diverse, can converge in diasporic communities, shaping how parents interpret and respond to their children’s needs.

Even when diagnosis is accessible, the stigma surrounding non-apparent disabilities remains pervasive. Individuals with such disabilities often face pressure to prove their legitimacy, navigating between hypervisibility and erasure. Like white-passing people of color, they exist in liminal spaces, “stuck between two worlds.” Their struggles are compounded by an ableist culture that values productivity and conformity. In schools, this manifests as exclusion: Girls with non-apparent disabilities are deemed lazy, disruptive, or inattentive rather than understood.

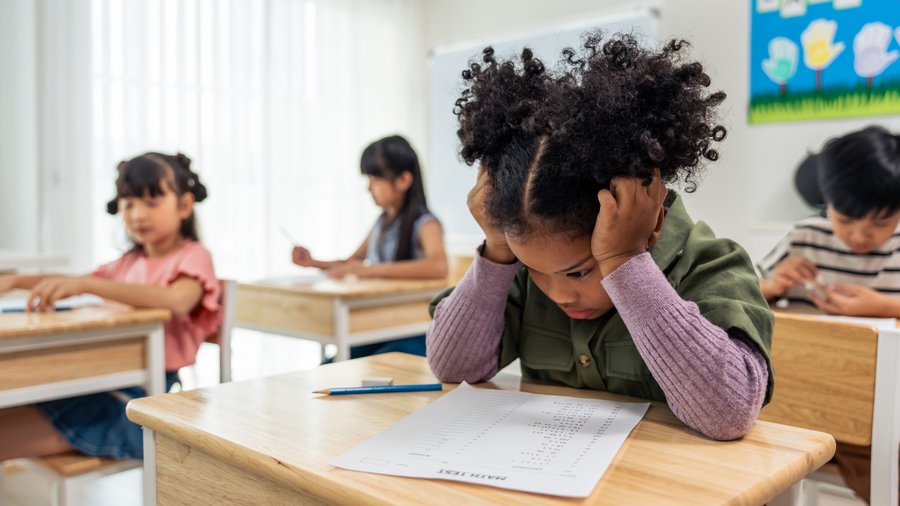

The consequences are severe. Educational systems in the West are increasingly designed around standardization and performance. In this context, diversity becomes a liability. Children who deviate from normative expectations — particularly if they are non-white, female, and disabled — are pathologized or pushed to the margins. Teachers, often lacking training in neurodiversity or cultural competency, misinterpret behaviors rooted in disability as willful defiance or academic failure. The result is misdiagnosis, underdiagnosis, and, eventually, criminalization.

Black girls’ non-apparent disabilities are often misread as misbehavior, resulting in disproportionate disciplinary action, while their experiences remain marginalized in disability narratives centered on whiteness and masculinity.

Gender adds another layer of complexity. Non-apparent disabilities often present differently across genders, yet research remains skewed toward male patterns. Conditions like autism and ADHD are underdiagnosed in girls, who may internalize their struggles or mask their symptoms. Patriarchal expectations around docility, emotional regulation, and femininity further obscure these diagnoses. Shame, too, plays a central role. In many cultural contexts, a disabled girl is seen not just as different, but as broken, unsuitable for marriage or motherhood.

These systemic exclusions have long-term repercussions. Girls with non-apparent disabilities are more likely to experience social isolation and mental health issues, and face significant obstacles in higher education and employment. The accumulation of stigma, neglect, and misrecognition becomes a cycle of deviancy — a self-fulfilling prophecy in which exclusion produces the very behaviors it punishes.

Despite this grim reality, change is possible. What is needed is not merely reform, but an epistemic shift — one that reorients education around care, context, and justice.

This begins with building long-term goals for inclusion and learning reforms that prioritize sustainable transformation over performative, short-term metrics. Inclusion is not a box to tick, but a culture to cultivate — one that embraces the full complexity of marginalized students' lived realities.

We must end the segregation of disabled students and instead invest in truly inclusive learning environments that are adaptive, flexible, and responsive. This includes centering healing within educational frameworks — acknowledging the trauma that systemic racism, ableism, and gendered violence inflict on children. Schools cannot be sites of learning without first being sites of safety.

Diagnostic practices must be rethought. Professionals and educators alike should be mandated to receive regular training on intersectionality, neurodiversity, and implicit bias — not as one-off workshops, but as part of ongoing professional development. We must diversify diagnostic tools and allow for holistic assessments, including sustained observation of students not only in classrooms but also in informal settings like play, recess, and peer interactions. This allows educators to better recognize social masking and context-dependent behaviors.

Classrooms must become spaces of recognition and empathy. This means integrating storytelling and narrative practices that allow students to articulate their experiences on their own terms. It also means incorporating body education into the curriculum — from mental health and nutrition to disability literacy — so that children are encouraged to become aware of their needs and develop the language to express them. These tools can help dismantle internalized shame and foster a sense of embodied agency.

Families are not external to this process — they are co-educators. Schools must actively promote positive family narratives that affirm children’s uniqueness and agency, rather than reinforcing stigmatization or medical authority. Parents should be welcomed as advocates and partners, with schools creating space for shared storytelling and intergenerational dialogue. These are not soft practices; they are political acts of solidarity.

To ensure these transformations last, schools must establish liaison roles — individuals trained in cultural mediation, disability rights, and youth work — who can bridge the gap between institutions and communities, particularly where stigma around disability persists. These liaisons can facilitate trust, navigate misunderstanding, and connect students to supportive networks.

Crucially, we must abandon the assumption that suffering must be visible to be legitimate. The focus on what can be seen — what can be documented or labeled — has systematically excluded those whose pain is subtle, chronic, or strategically masked. Recognition must extend beyond the visual and into the felt, narrated, and relational.

Non-white girls with non-apparent disabilities are not invisible. They are actively unseen. It is time we build systems of care that choose to see them — not through the lens of deficit, but through one of care, context, and justice.

We invite you to read and download the longer version of this article as a PDF here.

Iman Albertini is a graduate of the Centre International de Formation Européenne’s travelling Master program in Advanced European and International Studies, with a focus on the Mediterranean region. Currently working at the Department of Political Affairs and Human Development of the Organisation of African, Caribbean and Pacific States (OACPS), Iman was born into a French-Senegalese family and Iman grew up in Paris and the French Alps, fostering a passion for multiculturalism, sociology, and human rights.

The Salzburg Global Center for Education Transformation offers writing residencies at our inspiring home of Schloss Leopoldskron to thought leaders and educationalists working to advance the agenda of education transformation.

We invite partners who are interested in supporting these writing residencies to email Dominic Regester at .