Salzburg Global Fellow Raluca Andreea-Petrus explores the literary legacy of Japanese American writers in response to World War II internment camps

This article was written by Salzburg Global Fellow Raluca Andreea-Petrus, who attended the Salzburg Global American Studies program on “Crossing the Pacific: The Asian American Experience in U.S. Society and Discourse” in September 2024.

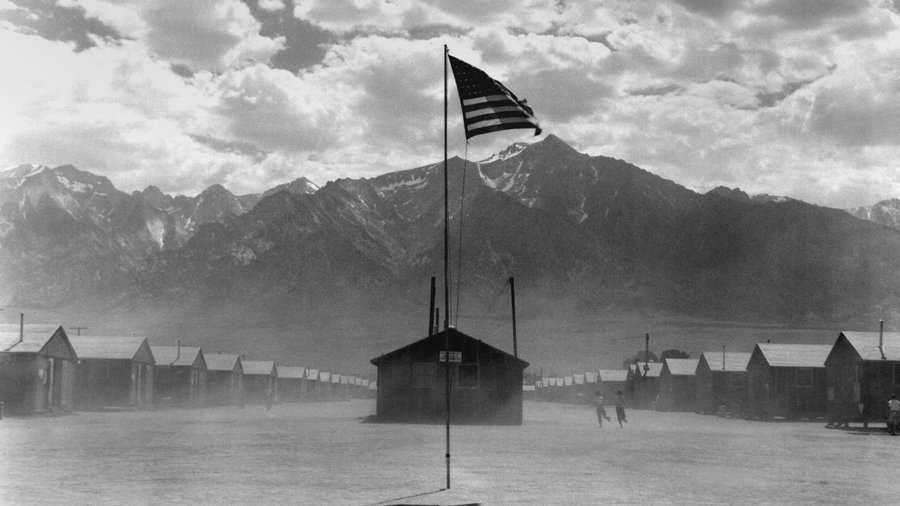

Japanese American authors often turn towards literature to express the coming-into-being of their community on American land, what they left behind, and how the journey developed in a new land and culture. Japanese American writers use their works to react to historical events and make their voices heard; they frequently represent themselves and their ethnic community members in a pursuit of home and acceptance, identity, and civil rights, deeply ingrained in historical and sociopolitical contexts. One phenomenon highly depicted by writers is the incarceration of Japanese and Japanese Americans in World War II, a process orchestrated by the U.S. government between 1941 and 1946.

To contextualize, as the U.S. was at war with Imperial Japan in 1941, people of Japanese ancestry in the United States, called "the Nikkei", were perceived as a risk because they shared ethnicity with the American wartime enemy. Following the Pearl Harbor attack, U.S. authorities perceived the Nikkei as a collective danger within U.S. borders who were meant to destabilize the country. Thus, the state forcefully removed and confined approximately 120,000 individuals in incarceration camps throughout the war, supposedly to protect the interests of the country and the safety of its people.

Such an act reverberated in the writings of camp survivors and their descendants, who felt the need to respond to the injustice and voice their experience through literature. The literature of Japanese American incarceration debuted soon after the closing of the ethnically charged imprisonment camps of the 1940s and continues today, thanks to the works of imprisonment camp survivors and their ancestors, i.e., second-generation ("Nisei") and third-generation ("Sansei") women and men. These authors include Miné Okubo, Monica Sone, John Okada, Hisaye Yamamoto, Lawson Fusao Inada, George Takei, and Julie Otsuka, to name a few.

For Japanese American writers of the second and third generation, civil rights and identity are co-dependent - one triggers the emergence of the other. For instance, in John Okada’s novel “No-No Boy”, the main character, Ichiro Yamada, struggles to find his place within American society, after being punished by the state through imprisonment. His double negation to two questions from the War Relocation Authority dismisses his status as a full citizen and weighs heavily on his self-esteem and ability to reintegrate. Thus, his “no-no” answers fracture his relationship with the state, his brother, and other community members, and eventually, a turn towards Americanness ruptures his relationship with his mother, rendering Ichiro in a post-incarceration identity quest once more.

Such an identity quest is pursued by characters depicted in graphic novels, such as “Citizen 13660” by Miné Okubo and George Takei’s “They Called Us Enemy”. In both books, the authors portray the experiences of incarceration through visual and textual means. Okubo’s drawings are joined by text descriptions, which were added after her liberation. Takei’s graphic novel, co-authored by Justin Eisinger and Steven Scott and illustrated by Harmony Becker, presents many instances of the Nikkei identity quest, anti-Japanese discrimination, as well as the depiction of divided loyalties, activism, and Nikkei and White solidarity.

In “No-No Boy”, “Citizen 13660”, and “They Called Us Enemy”, readers frequently encounter labels given to the Nikkei community, especially during World War II: “Jap”, “alien enemies”, “non-alien enemies”, “backstabbers”, “slant-eyed”, and “yellow peril”. Such labels, imposed by the state and the anti-Japanese feeling predominant in the 1940s, further segregated inter- and intracommunity relations in all the aforementioned literary works. These labels, stereotyping, and war hysteria decisively changed the destiny of the imprisoned Nikkei: The U.S. failed to apply the principle of checks and balances and, as a result, anti-Nikkei ethnic discrimination led to mass incarceration without due process.

Although differences may arise in genre particularities, author sensibility, and subject focus, all narratives express the consequences of ethnic discrimination faced by the Nikkei. As the state denied their civil rights and transformed them into “personae non-gratae”, the community’s sense of self suffered transformations: Inter- and intra-community tribalism decisively affected the identities of the Nikkei community, forcing individuals to take sides and break community and family bonds. Through their works, authors often ponder if their Japanese and American natures can co-exist in times of war or if one excludes the other: Such a positioning leads to marginalization or self-marginalization within their ethnic community and American society.

Raluca Andreea-Petrus is a research assistant at the Faculty of Letters, History, and Theology at the West University of Timisoara, where she teaches courses in English for practical purposes and contemporary English language. Raluca-Andreea earned a PhD in Philology in 2023 from the West University of Timisoara, with a thesis titled "Literary Expressions of The Japanese American Imprisonment Camps: Reconfigurations of Civil Rights and Identity".

Explore our digital publication, which includes more coverage from the Salzburg Global American Studies program on “Crossing the Pacific: The Asian American Experience in U.S. Society and Discourse.”